Historical keys and locks in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum began collecting iron- and locksmith work as early as 1852, at the founding of the museum. In the first catalogue Bautheile und Baumaterialien(Building Components and Building Materials) of 1868, August von Essenwein (1831-1892) remarked in his preface that the collection was still limited. He considered the collection of locksmith work especially important: “Few products are so well suited to express at first sight so clearly and palpably the spirit of the Middle Ages as the products of the craft, indeed art, of the locksmith“. His appeal to assign disposable building components to the museum was not in vain. The museum holds objects from all over Germany but the largest number comes from Nuremberg and the surrounding region.

The inventory records, as far as possible, the provenance of the pieces. Basically, one can assume that keys and locks were manufactured at the place where they were used. This is especially true of Nuremberg for the former imperial city had at its disposal outstanding locksmiths: Platschlosser (makers of large locks for doors and cupboards) and Glötschlosser (makers of padlocks). An exception are mobile padlocks.

In addition to the objects in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum should be counted the considerable holdings of the Gewerbemuseum (Arts and Crafts Museum), the former Bayerisches Gewerbemuseum in Nuremberg. Link: Collection Gewerbemuseum.

Craftsmen generally were classified according to the materials used for their crafts. However, this does not apply to smiths and locksmiths who both work with metals, whereby smith is the original professional designation. In contrast, locksmiths produced mechanically finer and artistically more demanding objects of smaller size than smiths.

The highest level of specialisation can be observed with those craftsmen who worked with iron, leading to the greatest possible perfection in Nuremberg. The intense division of labour furthermore made it possible to reduce working processes to the shortest possible period of time, which in turn reduced manufacturing costs. The market was amply provided with Nuremberg products. Because of the division of labour in the various areas, the number of workshops processing wrought iron increased. In the 16th century, more than half the craft workshops handled metals, making them almost five times more powerful than the textile trade.

Although Nuremberg did not possess any iron-ore deposits, the city developed into a centre for ironwork. Here the differentiation of craftsmanship was carried out to the smallest detailleading to extensive specialisation and the best possible use of resources and labour. However, because of the strict limitation of workers, production remained in the hands of workshops with few employees; it had not yet reached the level of manufacture. The iron-ore deposits in the neighbouring Upper Palatinate provided the necessary condition for the flourishing of the metal working trade in Nuremberg.

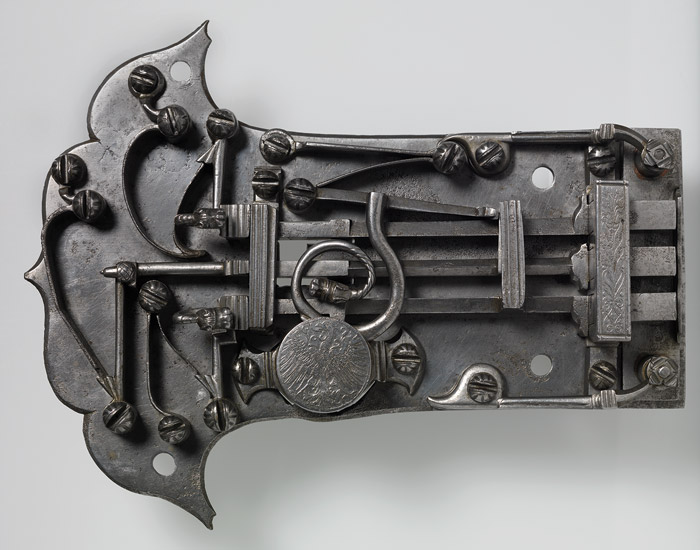

The museum possesses romanesque and gothic keys, two keys to the Nuremberg city gate, Venetian keys and key hangers. Of special interest are a key from the monastery at Maulbronn, a chamberlain key and a smoking pipe key. Also in the collection are door locks of the old Nuremberg city hall; a padlock of wrought iron; spherical padlocks in different sizes, down to the size of a pea; complicated puzzle locks for chests; and a door lock from Bayreuth made in 1837 as a masterpiece.

Publication

Manfred Welker, Historische Schlüssel und Schlösser im Germanischen Nationalmuseum. Bestandskatalog. Nürnberg 2014.

Team

Dr. Manfred Welker, associate Scientist

Further objects of research

Information and Services

Plan Your Visit

Opening Times

Location and Approach

GNM Museum Shop

FAQ

Library

Branches

Contact